|

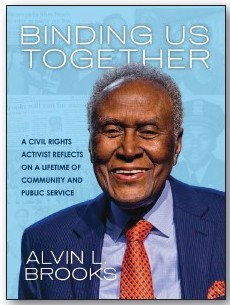

For years CRES has been encouraging others and other organizations to promote interfaith understanding -- as early as 2005 when we moved the Interfaith Council from a program of CRES to independence. Still, CRES continues to play a leadership role in the community, often "behind the scenes," while we are thinking long-term, beyond what will be our 40th year in 2022. While encouraging others, we have in fact offered new programs and co-sponsored events where our support was desired. We have continued, with the leadership of David Nelson, to offer the monthly Vital Conversations. Our continually updated website remains an extraordinarily valuable resource for interfaith understanding. Less publically, we advise and respond to indivdiuals and organizations seeking various sorts of help, from program design, request for speakers, contact information, and personal consultation about interfaith problems. One example which made it into the paper was our concern about an anti-Muslim cartoon through a letter written by the Interfaith Council. Whether I am wise or not, it seems the longevity of CRES leads folks to consult with us as they consider their own contributions to enlarging the meaning of a religiously-healthy community. This year it was a special joy to share in the announcement of Binding Us Together, the memoir of our beloved Alvin Brooks, for which I was developmental editor. Al has been a leader in interfaith understanding for decades as well as a leader for racial and every other form of justice, honored even by a President of the other party. Below as you scroll down, you will find notices and photos (and some texts) about other worthy activities in 2021, including an unexpected award from The Shepherd's Center. As minister emeritus, my work for CRES is volunteer. Many of you know I am often asked to officiate at weddings, memorial services, and baptisms, and I donate the money that generates to CRES. This and your support, makes it possible for CRES to pay its bills and provide what the community obviously continues to find as meritorious service and leadership. Thank you.

Vern Barnet CRES minister emeritus |

| Except for monthly Vital Conversations convened by David Nelson, CRES programs arise by request. Our management principle is "management by opportunity." Every year we are delighted by the number of opportunties given to us, as, for example, last year's list demonstrates. (Of course we also provide free consulation to organizations and other services as requested, not listed on our public website.) |

Transcendent meanings from COVID-19?

#MLK King Holiday Essay — Download a PDF of Vern's 2-page summary of the genius of the spiritual approach of Martin Luther King Jr by clicking this link. #210209Brooks About His Memoir Binding Us Together A Civil Rights Activist Reflects on a Lifetime of Community and Public Service February 9 Tuesday 1 pm via Zoom.

When I came to Kansas City

in 1975, I heard about someone speaking the truth about the racial situation,

and I soon heard him speak in person. As the years passed, I came to know

Al Brooks and understand why he was so important to the community and beyond.

Alvin L. Brooks is a former Kansas City police officer, councilman, and mayor pro-tem, as well as the founder of the community organization AdHoc Group Against Crime. His decades of civil rights, violence prevention, and criminal justice advocacy led President George H. W. Bush to appoint him to the President’s National Drug Advisory Council and Governor Jay Nixon to appoint him to the Kansas City Board of Police Commissioners. Brooks has also worked as a business consultant, motivational speaker, and lecturer, conducting hundreds of seminars about cultural/racial diversity, religious tolerance, and civil rights. He recently was named the 2019 Kansas Citian of the Year by the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce, and he’s a recipient of the Harry S. Truman Award for Public Service. Brooks currently lives in Kansas City among family and friends. In Binding Us Together, Alvin Brooks, Kansas City’s most beloved civil rights activist and public servant, shares a lifetime of stories that are heartfelt, funny, tragic, and inextricably linked to our nation’s past and present. Few people have faced adversity like Alvin Brooks. He was born into an impoverished family, nearly lost his adoptive father to the justice system of the South, and narrowly survived a health crisis in infancy. All the while, he was learning how to navigate living in a racist society. Yet by rising to these challenges, Brooks turned into a lifelong leader and a servant of his community. He shares personal anecdotes over the years about caring for his family, supporting Black youth, and experiencing historic events like the 1968 riots through his eyes. Told in a series of vignettes that follow pivotal moments in his life, Brooks’ uniquely personal yet influential story of activism and perseverance provides a hands-on guide for future generations. More relevant than ever to society today, his life’s work has been to better his community, make the world fairer for all, and diminish bias and discrimination. Alvin Brooks proves that a good heart, a generous spirit, and a lot of work can connect the world and bind us together.

Vern gazes with delight at a pre-publication copy

of the book for which he was developmental editor. Its Black History Month

publication date is Feb 23.

DedicationALSO February 23 Tuesday 6:30 PM, Al speaks with Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas via YouTube live-steam arranged by Rainy Day Books. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCoPIDBl45-cTvTsiDYi8jxQ AND

Learn more about Al and the book here. TECHNICAL UPDATE Last November, the Funeral Consumers Alliance of Greater Kansas City and CRES, co-sponsor, presented Medical Assistance in Dying

The Panelists were Peg Sandeen: National Executive Director of Death With Dignity. (keynoter) -- Fr. Thomas Curran, S.J.: Rockhurst University President. (Roman Catholic perspective) -- the Rev. Melissa Bowers, MA, MPS - Chaplain, Kansas Clty Hospice and Palliative Care. (Protestant perspective) -- Mahnaz Shabbir: of Shabbir Advisors management consultants. (Muslim perspective) -- Dr. John Lantos: M.D., Director of Pediatric Bioethics at Children's Mercy Hospital and Professor of Pediatrics at University of Missouri-Kansas City. (Medical, ethical and Jewish perspective). CRES and the FCA-GKC board neither support nor oppose

MAID. Our interest is strictly educational, and this program, we feel,

is a significant offering to the public.

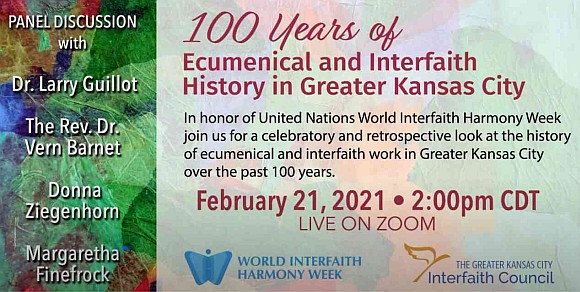

#210221-KC-History  2021 February 21 Sunday 2pm CDT

In honor of UN World Interfaith Harmony Week (WIHW), join us for a retrospective and celebratory look at the history of ecumenical and interfaith work in Greater Kansas City over the past 100 years. Cindy McDavitt (Chair of the Greater Kansas

City Interfaith Council) opens the program and the Rev Dr. Joshua Paszkiewicz

(Executive

Director of the Greater Kansas City Interfaith Council) introduces Geneva

Blackmer (founder, The Kansas City Interfaith

History Project and author of the Ecumenical and Interfaith History

of Greater Kansas City booklet, CRES Historian, and Program Director

of The Interfaith Center at Miami University). Geneva leads the discussion.

The program provides an overview of the project, followed by a panel disacussion with Dr. Larry Guillot, Vern Barnet, Margaretha Finefrock, and Donna Ziegenhorn. This presentation aims to provide a well-rounded perspective of where we have been, in the hope we may learn from the past, and collectively envision an even brighter future of interfaith work in Greater Kansas City. Panelists may address questions such as these:

Bio-sketches:

Donna Woodard Ziegenhornis a playwright and journalist. As a playwright, she focuses on non- traditional plays inspired by true stories collected in interviews. These plays bring forth life-shaping experiences of diverse individuals to dramatic performance. The Hindu and the Cowboy — which has been recognized by Harvard’s Pluralism Project for its unique contribution to building an inclusive community — grew from stories shared by people of numerous cultural and faith traditions across metropolitan Kansas City. The play has been seen by thousands of Kansas Citians in venues that range from public libraries to university stages, corporate training auditoriums to high school gymnasiums and interfaith conferences to stages beyond Kansas City. Donna and The Hindu and the Cowboy have received awards from the Crescent Peace Society, the Greater Kansas City Interfaith Council, Missouri Association for Social Work and Dialogue Institute Southwest. Maggie Finefrock

is currently Chief Learning Officer of The Learning Project, an organizational

development firm based in Kansas City, working internationally to create

high achieving, diverse and dynamic learning organizations: bridging people,

cultures, ideas, and resources through out the known universe.

Vern Barnet

founded the CRES, the Center for Religious Experience and Study in 1982,

40 years ago. In 1994 the Kansas City Star hired him to write a weekly

column featuring religious diversity which continued for 18 years. He is

associate professor of religious pluralism at Central Seminary. Author,

editor, and contributor to dozens of articles and several books. Binding

Us Together, the memoir of Alvin Brooks, for which he was developmental

editor, will be published this Tuesday as part of Black History Month.

A full bio appears here.

REASONS FOR SUCCESS OF EFFORTS

LIKE "GIFTS" CONFERENCE

SUGGESTIONS FORWARD

#tributeSheila TRIBUTE TO SHEILA SONNENSCHEIN One of Kansas City's most remarkable, talented, and dedicated interfaith leaders is Sheila Sonnenschein who was honored at the March 8 meeting of the Greater Kansas City Interfaith Council. Below is the opening tribute by Mary McCoy, herself one of our most distinguished interfaith leaders. We have added some photos and links to Mary's remarks.

#210413  SevenDays

2021 SevenDays

2021

Mindy Corporon, who suffered the horror of the murder of her father, William Corporon, and a son, Reat Underwood, by a white supremist religious fantatic who also murdered Terri LaManno, April 13, 2014, has turned grief to promoting understanding by creating Faith Always Wins Foundation st with its three pillars, kindness, faith and healing. SevenDays - Make a Ripple, Change the World, is its annual event. While CRES has no formal affiliation, we offer enthusiastic support. One of the virtual programs, April 19, is an interfaith discussion with Bill Tammeus, Moderator; the Rev. Gar Demo, Christianity; Saaliha Khan,Islam; Dr. Joshua Paszkiewicz, Buddhism; and Rabbi Sarah Smiley, Judaism.

#210418Tammeus Archived

YouTube Link

9/11: PERSONAL LOSS AND PUBLIC LESSONS

Vern interviews Bill Tammeus

about his extraordinary new book

"The people who perished on 9/11 -- whether as airline passengers, first

responders, office workers or others who simply were in the wrong place

when catastrophe struck -- must be remembered and their legacies honored.

One way that can happen is by each of us committing ourselves to being

thoughtful, loving people who can help lead others away from violent extremism

rooted in misguided theology. To make that commitment, start by reading

this book. Then share it with others," writes best-selling author and pastor

Adam Hamilton, whose Kansas City-based church has become the nation's largest

United Methodist congregation.

#210516Racism White Responsibility:

What responsibility

do white people have in ending structural racism?

.

#100YearsHistory Video Recording Just Released! (May 19) link

Contents by minute/second (approximate):

#210531

Vern writes:

This

year, on May 30, the Kansas City Star published this photo (that's me holding

the flag, facing the police, with Henry Stoever of PeaceWorks Kansas City

with the cap) with a guest

column by Tom Fox, retired editor and publisher of the National Catholic

Reporter. The photo was taken several years ago at the annual Memorial

Day protest 10-mile march from what used to be Bendix/Allied Signal to

the new Honeywell facility which produces 85% of the non-nuclear material

used in our nuclear bomb arsenal.

One way of understanding 20 years since 9/11 While the 9/11 attacks 20 years ago opened the gates of hell, the way our government has responded has brought us inside hell's domain. The smoke from that day, the acrid fumes, amplified into war, brings us purblind to the charred and hobbled Body Politic. How do we understand what has happened? How do we move forward?

1. Before 911, terrorism had been dealt with as a CRIME, internationally and at home. The violation of life and property in an otherwise orderly society makes the terrorist an especially despised outlaw. We employ a legal system to assure justice by punishing the criminal and removing the criminal from society. International courts have done the same. 2. But since September 11 we have used a WAR metaphor. Of course the metaphor is hardly new. We love war. We have fought the war against poverty and the war against drugs, though it is hard for us to admit defeat, even though Vietnam and Afghanistan are history now. We still fight the war against cancer, against crime, against . . . you name it. But a war against terrorism was new. The metaphor had power because we struggled not just against isolated attack but against an organized force seeking not just advantage through harm of a target but rather destruction of a government or civilization. Though we ourselves use violence, we assumed our own righteousness would bring us victory over evil. Both of the metaphors of crime and war too easily commend themselves because they are simple, and rest on the assumption that we are wholly good — and our opponents are completely evil. 3. A third metaphor might come closer to the complexity of the situation: DISEASE. Here the metaphor suggests not two separate, competing powers but of all humanity as a sick body, within the organs of communities, cities, and nations, afflicted in various ways, degrading or sustaining each other in different degrees, infected with individuals and groups poisoned (using Buddhist language) with greed, fear, and ignorance. Now, with COVID, we are learning that, as Martin Luther King said, “Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” Just so, CRES insists that the three great crises of our time, in the environment, in personhood, and in the social order, are all intertwined. And that the world's Primal, Asian, and Monotheistic traditions, respectively, provide the therapy to heal the planet, revivify personhood, and restore social order. Let us bring the healing powers of generosity, fellowship, and understanding to one another, expanding a circle of joy in service. Vern

On the first anniversary of 9/11, CRES opened a day-long observance beginning with a water ceremony between City Hall and the Federal Justice Center, later shown on national CBS-TV. Click here to see a 3-minute excerpt from that ritual.

Vern offers his conclusions

from 50 years of experience and study: in a troubled world, what paths

lie forward? and how can one dare offer praise for the intertwined mix

horror and beauty of existence?

September 23 Thursday 6:30-7:30pm Annual TABLE OF FAITHS “From the Front Lines: Spirituality in Times of Crisis” honors chaplains, first responders and many others who have played such a critical role in our lives these past months. A Virtual Fundraiser and Signature event of the Greater Kansas City Interfaith Council now independent but originally a program of CRES. Vern Barnet founded the Council

in 1989 and is Council Convener Emeritus. The Council newsletter has

published his brief notes about three

milestones in the early history of the Council.

Kansas City Star 2021 November 21

Brookings, Oregon - Charles Williams Stanford left

this world October 8th, 2021 in Brookings, Oregon. He was born in Overland

Park, Kansas to Lorraine (Williams) and Henry Stanford. He attended UMKC

and received a degree in psychology. His first job was as Art Director

at the Gillis Home for Children, where he met his wife, Mary. He made many

close friendships there that lasted long after he had moved on to pursue

other careers.

---- Lama Chuck Stanford was presented the Vern Barnet Interfaith Service Award at the 2016 annual Interfaith Thanksgiving Dinner, run by CRES for its first 25 years, now by ADL which began the awards in 2010 in continuing cooperation with the Greater Kansas City Interfaith Council. In his acceptance remarks, Lama Chuck repeated the core theology of CRES which locates the sacred in three dimensions, nature, personhood, and the human species: "We are facing environmental, personal, and societal crises that I think can best be solved by groups of different faiths working together for common solutions."

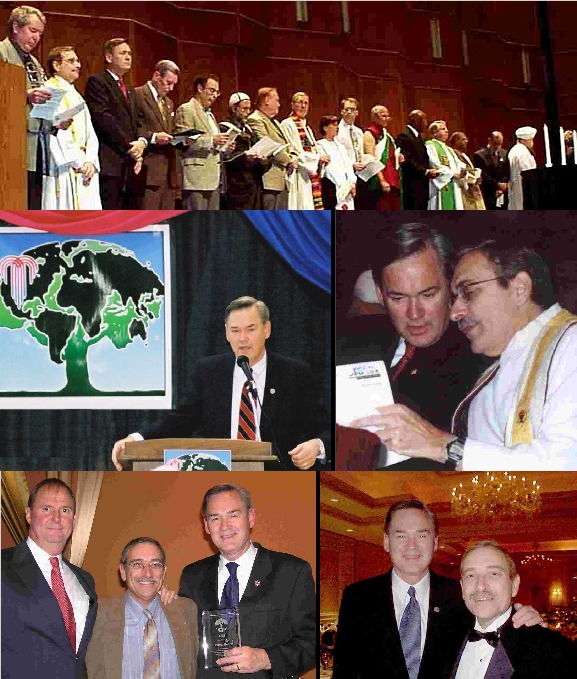

Dennis Moore: An Interfaith Champion Dennis Moore (1945-2021) was a man of many blessings for his constituents, his community, and the nation, and at CRES we especially cherish his work on behalf of interfaith understanding. When I moved from Pennsylvania to Kansas City in 1975, I heard about a remarkable young man, Dennis Moore, who had just been elected Johnson County District Attorney; so that winter I went to his swearing-in ceremony, along with a few dozen others, at most. I did not hear a carillon pealing, but I did hear a deep sense of decency and commitment. He served in that role well, and was elected in

1998 to the first of six terms as US Congressman from the 3d Kansas District,

a post usually held by a member of the

I was riveted a couple days after 9/11 to receive a call from him asking the Interfaith Council, which was to meet that night, to prepare an observance Sunday for the metro area. We did, and of course we asked him to be one of the speakers, along with a prominent Christian, Jew, and Muslim. It was a front-page story in Monday's Kansas City Star. (You'll recognize him as third from the left in the top photo.) Six weeks later he joined other distinguished speakers at what remains the area's only major interfaith conference. (Second row, left photo.) On other occasions he and his office worked with CRES to better secure and expand interfaith understanding. In 2003, CRES recognized him with our annual Thanksgiving Sunday Interfaith Ritual Meal award "for his leadership in the community and the US Congress honoring the many paths of faith and the American tradition of religious freedom." In the photo is CRES Board Chair Joe Archias who presented the award to him. I am personally a bit amused by the photo of him

and me after I delivered the prayer at the annual Jewish Community Relations

Bureau recognition dinner one year simply because I don't know there is

another photo in existence anywhere of me wearing a tux; but you will understand

that I cherish the photo not because of attire, but because of his hand

on my shoulder as I remember him as a friend to me and to so many.

Interfaith Panel Conversation with Composer The 2021 November 11 Thursday 7 pm Youtube recording can be accessed here or from the church website.

Introducing the interfaith panel and leading with

questions were the Rev Carla Aday (senior minister at Country Club

Christian Church which hosted the panel and presents the performance) and

Ben A Spalding (founder and artistic director of Kansas City’s Spire

Chamber Ensemble and Baroque Orchestra, which performs the work Nov 20.).

Composer

bridges Indian and classical worlds.

BY PATRICK NEAS

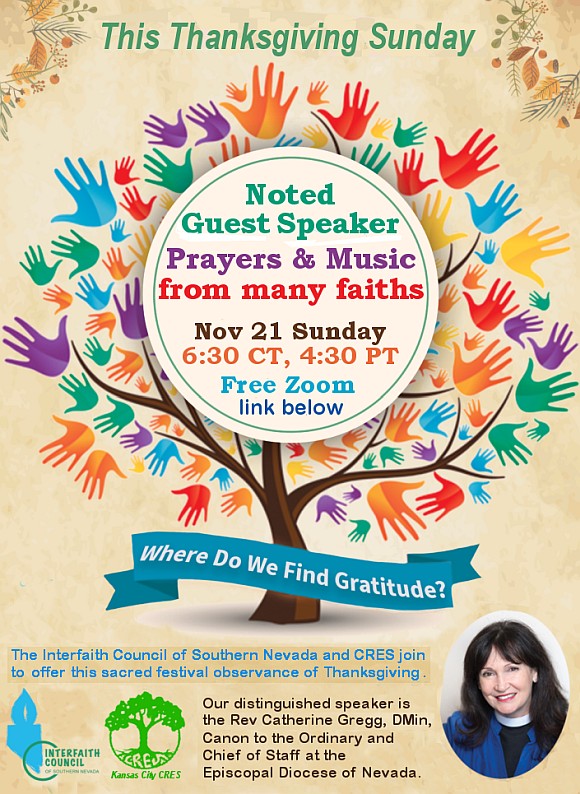

[ PHOTO: Indian American composer Reena Esmail used texts from the world’s religions to create “This Love Between Us.” ] “The Lamps may be different, but the Light is the same." “All religions, all this singing, one song.” Those lines by the Sufi poet and mystic Rumi are just part of the texts taken from the world’s religions and set by Indian American composer Reena Esmail in her choral work “This Love Between Us.” The work celebrates what unites the world’s various faiths, especially the concept of the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Recognizing the universality of Bach’s music, Esmail wrote “This Love Between Us” to be performed on the same program as the Lutheran composer’s Magnificat. The Spire Chamber Ensemble conducted by Ben Spalding will perform both works on Nov. 20 at Country Club Christian Christian Church. The concert will celebrate the 100th anniversary of the church. The concert will also mark the first time the Spire Chamber Ensemble has presented a live indoor concert since its performance of Bach’s Mass in B minor on March 7, 2020. For this important event, Spalding thought Esmail and Bach would fit the bill perfectly. “It just didn’t feel right to not address what we’ve all been through the last 18 or 20 months,” Spalding said. “The pandemic, the loss of life, as well as the political discord, the social unrest. We wanted a piece that would comment on the world around us and to use the power of text to promote better things, to promote unity and how we are more alike than we are different.” Esmail’s text draws on everything from various Buddhist sutras to one of the Upanishads and St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. “She incorporates all these major religions, Buddhism, Sikhism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Jainism and Islam,” Spalding said. “We have to sing in seven Hindustani languages, which are completely different from anything we’ve ever done before. The composer is coaching us. She’s made a wonderful audio guide and has done separate coaching with the various soloists.” Spalding says that Bach’s setting of Mary’s hymn of praise is an ideal complement to Esmail’s work. “A lot of scholars look at the Magnificat as a social justice piece because the text is about the lowly being lifted up and the proud being brought down,” he said. “That would have been quite the political statement. Especially the way Bach sets it. Reena sees the connection between her work and how the Magnificat focuses on social justice issues.” Bach composed the Magnificat as a celebratory work after he got the job as music director at St.Thomas Church in Leipzig. And he pulled out all the stops, using a full baroque orchestra including trumpets and timpani. The Spire Chamber Ensemble will perform the work on authentic period instruments. Esmail was drawn to not only the message of Bach’s Magnificat, but also its instrumentation. “This Love Between Us” is one of the very few contemporary works written for authentic period instruments of the 18th century. There will, however, be the intriguing addition of sitar and tabla. “Rajib Karmakar is coming from L.A. to play the sitar,” Spalding said. “It’s a very demanding, virtuosic sitar part. And Amit Choudhury will play the tabla, the classical Indian percussion instrument.” Spalding says the concert is a fitting way to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Country Club Christian Church, a congregation noted for its commitment to social justice. “‘This Love Between Us’ is powerful and asks questions,” Spalding said. “That’s the goal of art, to ask questions and to consider other people’s stories. And then that teaches us empathy. I think it will be a beautiful gift to our Kansas City community.” 7:30 p.m. Nov. 20. Country Club Christian Church, 6101 Ward Parkway. Free but reservations required. spirechamberensemble.org. [ PHOTO: Spire Chamber Ensemble is set to perform Nov. 20, the first time since the pandemic began. Eric Williams ] ------ Other than proclaiming the wisdom of the world's religions to resolve the three great crises* the world faces, CRES emphasizes the value of diversity of faiths, just as a healthy eco-system depends on a rich diversity of species. Nonetheless, as people of various faiths increasingly encounter each other, two extreme opinions are particularly interesting: (1) religions are basically alike,** and (2) religions are fundamentally distinct. Which view is better? November 14 Sunday 4-5:15 pm CT INTERFAITH THANKSGIVING GATHERING “Promoting Interfaith Peace, Renewal and Regrowth”

FREE online interfaith gathering -- including interfaith prayers of gratitude. ADL and GKCIFCHosted by Heartland Chapter of the Alliance of Divine Love Co-sponsored by Greater KC Interfaith Council https://www.facebook.com/events/793753937932632

YouTube Reccording of the ADL and GKCIFC program The annual observance was sponsored by CRES

for its first 25 years.

Here is the

YouTube link to the recording of the program.

THANKSGIVING, EVEN WITH MANY FAILURES Organizationally, my failures are

glaring, including, for example, an inadequate transition from the Interfaith

Council as a meaningful program of CRES to an independent status in 2005,

continuing without the resources it needs and deserves. Many other organizations,

without a comprehensive vision, often unaware of each other, are filling

some gaps. Thank God for their efforts, and yours.

--Vern

OTHER ANNOUNCEMENTS

Having spawned several other organizations, including the Greater Kansas City Interfaith Council, we continue to offer programs initiated by and through others but we no longer create our own in order to focus on our unique work. For interfaith and cultural calendars maintained by other groups, click here. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2022 PROGRAMS |

A Free Monthly Discussion Group Led by David E Nelson C R E S senior associate minister president, The Human Agenda “The purpose of a Vital Conversation is not to

win an argument,

in dialog that will add value to the participants and to the world. In Vital Conversations, we become co-creators of a better community. —David Nelson The discussions began May 24, 2002, at the CRES facility by examining Karen Armstrong’sThe Battle for God

2021 Vital Conversations Schedule

#vcJan

----

Releasing Conversation: Do you believe human beings are inherently good (Planet A) or inherently bad (Planet B)? Why? What difference does it make which you believe? Did you watch the events January 6th in Washington D.C. while it was happening? Describe your feelings then. What are your feelings today about the United States? Who have you talked with about your feelings? 1. Veneer Theory – “The notion that civilization is nothing more than a thin veneer that will crack at the merest provocation. In actuality, the opposite is true. It’s when crisis hits - when the bombs fall or the floodwaters rise – that we humans become our best selves.” (p. 4). Share a story from your experience that illustrates this. 2. Placebo effect – “If your doctor gives you a fake pill and says it will cure what ails you,chances are you will feel better. The more dramatic the placebo, the bigger that chance…If you believe something enough, it can become real…We are what we believe. We find what we got looking for. And what we predict, comes to pass.” (p.8-9) Nocebo effect – “Warn your patients a drug has serious side effects, and it probably will. If you believe something enough, it can become real.” (p.9) Ashil Babbitt died inside the Capital on January 6th. What do you think she believed? Why did she believe these things? What did the tens of thousands who participated in rally in Washington believe? 3. Compare the two stories; Lord of the Flies by William Golding and the real event told by Peter Warner. 4. “In one corner is Hobbes: The pessimist who would have us believe in the wickedness of bhuman nature. The man who asserted that civil society alone could save us from ourbaser instincts. In the other corner, Rousseau: the man who declared that in our heart of hearts we’re all good. Far from being our salvation, Rousseau believed civilization is what ruins us.” (p. 43-44). Which corner do you stand in? Can you make the case with personal stories? “That’s how our sense of history get flipped upside down. Civilisation has become synonymous with peace and progress and wilderness with war and decline. In reality, for most of human existence, it was the other way around.” (p.110). What does the author mean by this? 5. What did you learn from the Easter Island story? The Stanford Prison Experiment? The Stanley Milgram’s Laboratory? “Hannah Arendt argued that our need for love and friendship is more human than any inclination towards hate and violence. And when we do choose the path of evil, we feel compelled to hide behind lies and cliches that give us a semblance of virtue.” (p. 173). Does your personal experience and observation agree with her? “Belief in humankind’s sinful nature also provides a tidy explanation for the existence of evil. When confronted with hatred or selfishness, you can tell yourself, ‘Oh, well, that’s just human nature. But if you believe that people are essentially good you have to question why evil exists at all. It implies that engagement and resistance are worthwhile, and it imposes an obligation to act.” (p. 174) When have you benefited by using communication and confrontation, compassion and resistance? 6. Had you heard about the death of Catherine Susan Genovese before readying Humankind? Why did this story get retold so often? 7. “Tactics, training, ideology – all are crucial for an army, Morris and his colleagues confirmed. But ultimately, an army is only as strong as the ties of fellowship among its soldiers. Camaraderie is the weapon that wins wars.” (p. 205-206) If you were in the military would you agree? If you know men or women in the military would you agree? “Terrorists don’t kill and die just for a cause…They kill and die for each other.” (p.208) 8. “Infants possess an innate sense of morality. Infants as young as six months old can not only distinguish right from wrong, but they also prefer the good over the bad.” (p.209) What does the author suggest has been done to train human beings to hurt and kill others? Military friends, is this your experience? What would it take for you to kill another person? 9. Power Paradox – “Scores of studies show that we pick the most modest and kindhearted individuals to lead us. But once they arrive at the top, the power often goes straight to their heads – and good luck unseating they after that.” (p. 229) Why do you think 75 million Americans voted for Donald Trump in the recent election?

11. “Play is not subject to fixed rules and regulations but is open-ended and unfettered. Unstructured play is also nature’s remedy against boredom…Dutch historian Johan Huizinga christened us HOMO LUDENS – ‘playing man’. Everything we call ‘culture’ originates in play.” (p. 282-283). How do you play? When was the last time you really played? 12. “Hatred and racism stem from a lack of contact. We generalize wildly about strangers because we don’t know them. So the remedy seemed obvious: more contact. After all, we can only love what we know” (p.352) In order to “stay human” who can you contact in the near future? What other ways can you “stay human.” Another great discussion! ----

If you wish to believe that people are naturally good but you can’t because of the counter examples in the news and you’ve been taught otherwise in history, sociology, and psychology school classes, then you need to read this book. This book makes a convincing case that humans are by nature friendly and peaceful creatures, and most of the counter examples are caused by pressures of civilization for which evolution of the human brain has left us ill-prepared. Bregman makes the case that a probable reason Homo sapiens prevailed during the prehistory era over Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo erectus is because we were hard-wired to be social, work in groups, and consider what’s best for the collective community. This predisposition worked well over many years while humans lived as hunter-gatherers. But these same tendencies led to violent behavior when subjected to the territorial concerns and concentrated populations of the civilized world. The predisposition for protecting the collective community in the hunter-gatherer world transformed into xenophobia in the civilized world. The book attacks the commonly accepted truths about human nature described in the novel Lord of the Flies, and presents as a counter example a true historical instance of young boys marooned on an island in which successful cooperation was exhibited. Also, a reinterpretation of the true facts surrounding the famous 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese is provided that demonstrates the tendency of news articles to exaggerate and falsify sensational aspects of a story. Bregman also deconstructs the bad science and/or lazy reportage contained in many famous sociological case studies that have claimed that civilization is but a thin fragile coating protecting us from dangerous human nature. Some of the better known debunked studies are the Stanford Prison experiment and the Milgram experiment. The book also makes the case that the chief motivation for soldiers to fight in war is the spirit of camaraderie, not ideology. The second part of the book is devoted to proposing ways to structure work, school, and organizations that can utilize true human nature for optimum beneficial results. Many of these example argue that when we expect better, we very often get better. Examples given include an exemplary Norwegian prison, Nelson Mandela and the end of Apartheid in South Africa, challenging playgrounds for children, and unstructured schools. Bregman repeatedly

notes that even though civilization has bred into the human brain a suspicion

of people outside of our own group, our prejudices tend to fall away once

we come to know those “others.”

Here is a link to The Guardian story

with photos and additional text about the shipwreck and

rescue: the real boys actually created a cooperative society, just

the opposite of Golding's Lord of the Flies. I am a Pelagian because I think

Augustine's development of "original sin" and human

depravity misinterprets the Gospel. I rather believe in the

inborn goodness of babies (Jesus said, "Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven."), corruptible indeed as they grow and are

influenced by those around them or uplifted to greater

goodness by love. Rutger

C. Bregman's Humankind: A Hopeful History . *The

Anabaptist position is that one needs to know what is happening when

one is baptised by choice. Babies don't know and don't choose it. THE GUARDIAN 2020 May 9 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - #vcFeb

Quotationss and questions selected by David Nelson “America has an unseen skeleton, a caste system that is as central to its operation as are the studs and joists that we cannot see in the physical buildings we call home. Caste is the infrastructure of our divisions. It is the architecture of human hierarchy, the subconscious code of instructions for maintaining, in our case, a four-hundred-year-old social order. A caste system is an artificial construction. Throughout human history, three caste systems have stood out. The tragically accelerated, chilling, and officially vanquished caste system of Nazi Germany. The lingering, millennia-long caste system of India. And the shape-shifting, unspoken, race-based caste pyramid in the United States.” (p.17) Is this a new idea for you? Have you thought of a “caste system” in America before? 1. “Caste and race are neither synonymous nor mutually exclusive. Race, in the United States, is the visible agent of unseen force of caste. Caste is the bones, race the skin. Race is what we can see, the physical traits that have been given arbitrary meaning and become shorthand for who a person is. Caste is the powerful infrastructure that holds each group in its place. Caste is fixed and rigid. Race is fluid and superficial, subject to periodic redefinition to meet the needs of the dominant caste in what is now the United States.” (p.19) Can you share examples from the book and from your experience? 2. “In the decades to follow, colonial laws herded European workers and African workers into separate and unequal queues and set in motion the caste system that would become the cornerstone of the social, political, and economic system in America. This caste system would trigger the deadliest war on U.S. soil, lead to the ritual killings of thousands of subordinate-caste people in lynchings, and become the source of inequalities that becloud and destabilize the country to this day.” (p41) Why did this happen? What made America unique? 3. “Slavery is commonly dismissed as a ‘sad, dark chapter’ in the country’s history. It is as if the greater the distance we can create between slavery and ourselves, the better to stave off the guilt or shame it induces. The country cannot become whole until it confronts what was not a chapter in its history, but the basis of its economic and social order. For a quarter millennium, slavery was the country. Slavery was part of everyday life, a spectacle that public officials and European visitors to the slaving provinces could not help but comment on with curiosity and revulsion. (p43). Why is it not enough to simply say “slavery was a sad, dark chapter” in our history? Why must we keep talking about it? Or do we? 4. “The idea of race is a recent phenomenon in human history. Geneticists and anthropologists have long seen race as a manmade invention with no basis in science or biology.” (p.65) Why do you think race became so important in the US? Why is it still so central to our identity and behavior? 5. “Hitler had studied America from afar, both envying and admiring it, and attributed its achievement to its Aryan stock. He praised the country’s near genocide of Native Americans and the exiling to reservations of those who had survived. Hitler especially marveled at the American ‘knack for maintaining an air of robust innocence in the wake of mass death.’” (p.81). “’Silence in the face of evil is itself evil.’ Bonhoeffer once said of bystanders. ‘God will not hold us guiltless. Not to speak is to speak. Not to act is to act.’” (p90) Why did we tolerate near genocide and mass death? What beliefs made this evil possible?

7. “The Eight Pillars of Caste: 1. Divine Will and the Laws of Nature; 2. Heritability; 3. Endogamy and the Control of Marriage and Mating; 4. Purity versus Pollution; 5. Occupational Hierarchy; 6. Dehumanization and Stigma; 7. Terror as enforcement; 8. Inherent Superiority verses Inherent Inferiority.” (pp99-167) Which pillar surprises you? Which pillar do you least understand? 8. “Thus, a caste system makes a captive of everyone within it. Just as the assumptions of inferiority weigh on those assigned to the bottom of the caste system, the assumptions of superiority can burden those at the top with expectations of needing to be several rungs above, in charge of all things, at the center of things, to police those who might cut ahead of them, to resent the idea of undeserving lower castes jumping the line an getting in front of those born to lead.” (p.184) Can you recall feeling the burden of being in an upper caste? Can you share a story about it? 9. “Everything that happened to the Jews in Europe, to African-Americans during the lynching terrors of Jim Crow, to Native American as their land was plundered and their numbers decimated, to Dalits considered so low that their very shadow polluted those deemed above them – happened because a big enough majority had been persuaded and had been open to being persuaded, centuries ago or in the recent past, that these groups were ordained by god as beneath them, subhuman, deserving of their fate. Those gathered on that day in Berlin were neither good nor bad. They were human, insecure and susceptible to the propaganda that gave them an identity to believe in, to feel chosen and important.” (p266) Can you recall a time you were “caught up”, persuaded, and willing to participate in action that was wrong and perhaps later identified as evil? 10. “What white people are really asking for when they demand forgiveness from traumatized community is absolution, ’Roxane Gay wrote, ’They want absolution from the racism that infects us all even though forgiveness cannot reconcile America’s racist sin.’ One cannot live in a caste system, breath its air, without absorbing the message of caste supremacy.” (p289) “Caste is more than rank, it is a state of mind that holds everyone captive, the dominant imprisoned in an illusion of their own entitlement, the subordinate trapped in the purgatory of someone else’s definition of who they are and who they should be.” (p290) Do you agree with Roxane Gay? What can we do today to bring healing, change, and hope? What are you doing to refuse cooperation with America’s caste system?

A different perspective almost always enhances understanding. Sometimes labeling with a different word can shape-shift a subject into a slightly different perspective revealing additional layers of meaning. I think that’s what Wilkerson has done by using the word “caste” to describe what others have described as structural, institutional, or systemic racism. The word “racism” alone doesn’t communicate the endemic nature of the problem that is at the core of society’s discontent. The meaning of “racism” is widely understood to be a personal attitude and that makes it difficult to comprehend the hidden sociological barriers that impose control on human relationships. Caste has traditionally been used in the English language to describe the rigid social stratification characteristic of Hindu society, a practice with ancient origins. Americans have generally regarded caste as a backward non-western custom that has nothing to do with the way we live. This book examines the characteristics of the Indian caste system, compares them with American racial behavior and history, and then convincingly makes the point that they share many similarities. The book further makes the point that the Nazi anti-Jewish laws were inspired and patterned in many ways on the American Jim Crow laws. Wilkerson isn't saying the three are identical, but that they share many similarities which can be used to help understand the difficulty of making changes. The book’s skillful interweave of interesting personal vignettes with abstract ideas provides a compelling reading experience. The stories of ordinary people from both the higher castes and of the lowest are shared providing numerous examples of the misplacement of human potential. The history of the laws and practices that have led to the current wealth disparities are reviewed. Most readers will be appalled at the repeated examples of terror and routine discourtesies that prompt a range of emotion varying from indignation to sorrow. I think this book provides a convincing case for the reality of American caste. But there's an implicit message that the possibility of change is futile. Elements of hope within this book are sparse. Still, if it leaves the reader better informed, it will have done some good. Here's a link to an excerpt from the book, Caste. Here's a link to another excerpt.: - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - March 10 Wednesday 1-2:30 p.m. on Zoom Siddhartha by Herman Hesse. In the novel, Siddhartha, a young man, leaves his

family for a contemplative life, then, restless, discards it for one of

the flesh. He conceives a son, but bored and sickened by lust and greed,

moves on again. Near despair, Siddhartha comes to a river where he hears

a unique sound. This sound signals the true beginning of his life -- the

beginning of suffering, rejection, peace, and, finally, wisdom.

Pages are listed to provide the

context of each question. Surely group members will be pleased to read

passages aloud.

This novel is a story about a man named Siddhartha who spends a lifetime seeking ultimate enlightenment. The story occurs during the time when the Buddha is still alive, so one would think there’s no need to seek further enlightenment after meeting him. Siddhartha is satisfied that the Buddha has reached ultimate enlightenment, but it’s impossible for his experience to be satisfactorily communicated to others by way of his teachings. Thus Siddhartha decides to move on to a life filled with a variety of experiences all the while seeking the meaning of truth—ascetic beggar, sex with a woman, luxurious life of wealth, simple life as a ferryman, love and care of a son, and the experience of his son leaving. So finally Siddhartha is on his death bed, he has finally achieved enlightenment, and his friend asks him what insight he has learned from life. Siddhartha replies with the following:His friend responds to this by saying that this is pretty much the same as what the Buddha taught; Why not simply be his follower? To this Siddhartha replies the following: "I know that I am in agreement with Gotama (a.k.a. the Buddha). How should he not know love, he, who has discovered all elements of human existence in their transitoriness, in their meaninglessness, and yet loved people thus much, to use a long, laborious life only to help them, to teach them! Even with him, even with your great teacher, I prefer the thing over the words, place more importance on his acts and life than on his speeches, more on the gestures of his hand than his opinions. Not in his speech, not in his thoughts, I see his greatness, only in his actions, in his life.”So there you have it—enlightenment! - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

1. Have you ever been in a meat packing plant? What was it like? The Jungle is considered “agitation rather than art”, according to Morris Dickstein. Sinclair himself insisted that his book was intended not as an expose of the meat industry but as an argument for socialism, to which he had recently been converted. Much socialist activity was happening in the US. Upton Sinclair was sent in 1904, by the publisher of “Appeal to Reason” in Girard, Kansas, to examine conditions in the stockyards of Chicago. The resulting novel, based on seven weeks of intensive research, was serialized and achieved great notoriety even before it came out as a book. The book begins with a Lithuanian wedding of Jurgis Rudkis and Ona Likoszaite, who become characters in the novel. They spend more than a year’s income on the wedding day feast (the veselija). “The veselija has come down to them from a far-off time; and the meaning of it was that one might dwell within the cave and gaze upon shadows, provided only that once in his lifetime he could break his chains, and feel his wings, and behold the sun. . . . Thus having known himself for the master of things, a man could go back to his toil and live upon the memory all his days.” (p. 12). 2. Why would people spend so much on a wedding? Why do you think the author begins the story with a wedding? “The stench was almost overpowering, but to Jurgis it was nothing. His whole soul dancing with joy – he was at work at last. He was at work and earning money!” (p. 44) 3. Have you experienced joy in a job? When and where? Did it last? This is a story of human challenge and tragedy. Jurgis buys and loses a house, his wife and children die, he confronts injustice in a variety of places and yet he presses on, even before discovering hope in politics. “Marija, who takes to prostitution to support the family and educate children, shows considerable growth, and our respect for her is enhanced. Elzbieta is the picture of the all-suffering, all-sacrificing, all-forgiving mother who, undaunted by the heavy odds against her, fights back.” (p. 83 Mookerjee) 4. Where does courage and persistence come from? How do you hang in there when the world seems against you? “He went on, tearing up all the flowers from the garden of his soul, and setting his heel upon them. The train thundered deafeningly, and a storm of dust blew in his face; but though it stopped now and then through the night, he clung where he was – he would cling there until he was driven off, for every mile that he got from Packingtown meant another load from his mind.” (p. 214) 5. Did Jurgis find a better life in the country? Why did he return to Chicago? How did you discover “your place” in the world? “ "The voice of the poor, demanding that poverty shall cease! The voice of the oppressed, pronouncing the doom of oppression! The voice of power, wrought out of suffering – of resolution, crushed out of weakness – of joy and courage, born in the bottomless pit of anguish and despair! The voice of Labor, despised and outraged; a mighty giant, lying prostrate – mountainous, colossal, but blinded, bound and ignorant of his strength. And now a dream of resistance haunts him, hope battling with fear; until suddenly he stirs, and a fetter snaps – and a thrill shoots through him, to the farthest ends of his huge body, and the banks are shattered, the burdens roll off him – he rises – towering, gigantic; he springs to his feet, he shouts in his newborn exultation---". (p. 307) 6. Have you experienced a “discovery” of such magnitude? Is this a “born again” experience? “The Socialist movement was a world movement, an organization of all mankind to establish liberty and fraternity. It was the new religion of humanity – or you might say it was the fulfillment of the old religion, since it implied but the literal application of all the teachings of Christ.” (p. 315) “A Socialist believes in the common ownership and democratic management of the means of producing the necessities of life and a Socialist believes that the means by which this is to be brought about is the class-conscious political organizations of the wageearners.” (p. 336-337). “I would seriously maintain that all the medical and surgical discoveries that science can make in the future will be of less importance than the application of the knowledge we already possess, when the disinherited of the earth have established their right to a human existence.” (p. 344) 7. How convincing is this novel and especially the speeches of the final chapters on your thinking about socialism?

This classic novel follows the life

of a young man who immigrated to the United States and settles in Chicago

during the early twentieth century together with his extended family made

up of his fianc?e and future in-laws. They're ambitious and hard workers,

but due to a combination of predatory house financing, draconian working

conditions, and corrupt business/governmental powers, their situation deteriorates

to the point of economic and social devastation—(i.e loss of their house

and death of his wife and son).

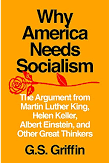

The city, which was owned by an oligarchy of business men, being nominally ruled by the people, a huge army of graft was necessary for the purpose of effecting the transfer of power. Twice a year, in the spring and fall elections, millions of dollars were furnished by the business men and expended by this army; meetings were held and clever speakers were hired, bands played and rockets sizzled, tons of documents and reservoirs of drinks were distributed, and tens of thousands of votes were bought for cash. And this army of graft had, of course, to be maintained the year round. The leaders and organizers were maintained by the business men directly—aldermen and legislators by means of bribes, party officials out of the campaign funds, lobbyists and corporation lawyers in the form of salaries, contractors by means of jobs, labor union leaders by subsidies, and newspaper proprietors and editors by advertisements. The rank and file, however, were either foisted upon the city, or else lived off the population directly. There was the police department, and the fire and water departments, and the whole balance of the civil list, from the meanest office boy to the head of a city department; and for the horde who could find no room in these, there was the world of vice and crime, there was license to seduce, to swindle and plunder and prey. The law forbade Sunday drinking; and this had delivered the saloon-keepers into the hands of the police, and made an alliance between them necessary. The law forbade prostitution; and this had brought the "madames" into the combination. It was the same with the gambling-house keeper and the poolroom man, and the same with any other man or woman who had a means of getting "graft," and was willing to pay over a share of it: the green-goods man and the highwayman, the pickpocket and the sneak thief, and the receiver of stolen goods, the seller of adulterated milk, of stale fruit and diseased meat, the proprietor of unsanitary tenements, the fake doctor and the usurer, the beggar and the “pushcart man," the prize fighter and the professional slugger, the race-track “tout,” the procurer, the white-slave agent, and the expert seducer of young girls. All of these agencies of corruption were banded together, and leagued in blood brotherhood with the politician and the police; more often than not they were one and the same person,—the police captain would own the brothel he pretended to raid, the politician would open his headquarters in his saloon. "Hinkydink" or “Bathhouse John," or others of that ilk, were proprietors of the most notorious dives in Chicago, and also the "gray wolves" of the city council, who gave away the streets of the city to the business men; and those who patronized their places were the gamblers and prize fighters who set the law at defiance, and the burglars and holdup men who kept the whole city in terror. On election day all these powers of vice and crime were one power; they could tell within one per cent what the vote of their district would be, and they could change it at an hour's notice.The story told by this book is so depressing that I couldn't help but wonder how the author was going the end the story. Surely he would find a way of adding a bit of optimism. Sure enough the author provides a vision for the future. It's called Socialism. One evening the story's protagonist happens to attend a speech promoting the socialist cause. The text for the equivalent of about a half hour speech is included in the book. It's clear that this is the message that the author wants to convey. Below I have included the beginning of this speech because I think it summarizes perfectly the life of our protagonist up to this point. And so you return to your daily round of toil, you go back to be ground up for profits in the world-wide mill of economic might! To toil long hours for another's advantage; to live in mean and squalid homes, to work in dangerous and unhealthful places; to wrestle with the specters of hunger and privation, to take your chances of accident, disease, and death. And each day the struggle becomes fiercer, the pace more cruel; each day you have to toil a little harder, and feel the iron hand of circumstance close upon you a little tighter. Months pass, years maybe—and then you come again; and again I am here to plead with you, to know if want and misery have yet done their work with you, if injustice and oppression have yet opened your eyes!So the book ends with a variety of conversations that defend the cause of socialism. The book suggests that support for it is trending up and that eventually will win nationwide popular support. So that's how things looked in 1906 when this book was published. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - May 12 Wednesday 1-2:30 p.m. on Zoom -- (Notes from last month) Why America Needs Socialism: The Argument from Martin Luther King, Helen Keller, Albert Einstein, and Other Great Thinkers by G.S. Griffin  This book presents a contemporary case for socialism built on the words

and ideas of history’s greatest leaders, thinkers, and artists. Exploring

their views and connecting them to present day struggles, Griffin is crucial

reading for anyone seeking to learn from the past in order to change today’s

world in revolutionary ways. Griffin participates in the discussion. David

suggests this article in Sojourners.

This book presents a contemporary case for socialism built on the words

and ideas of history’s greatest leaders, thinkers, and artists. Exploring

their views and connecting them to present day struggles, Griffin is crucial

reading for anyone seeking to learn from the past in order to change today’s

world in revolutionary ways. Griffin participates in the discussion. David

suggests this article in Sojourners.

1. “Capitalism is an economic system characterized by the private ownership of business and industry, where earning a profit by selling a good or service is each owner’s basic and necessary goal.” (p. 16) “Socialism is a political and economic theory of social organization which advocates that the means of production, distribution, and exchange should be owned or regulated by the community as a whole.” (New Oxford American Dictionary) What would you add to these two definitions to enhance a conversation about socialism in America? 2. “Many readers of faith believe that higher powers created humanity to be sinful by nature. Thus, it makes sense to many that capitalism is natural, and the way things must remain.” (p. 15) Do you agree that humanity is sinful by nature? How do you defend your opinion? 3. “Not only is it possible, but Einstein saw it as the true purpose of socialism; to keep growing, to keep bettering ourselves. Likewise, Mahatma Gandhi disbelieved in the supposed ‘essential selfishness of human nature’ because man can ‘rise superior to the passions that he owns in common with the brute and, therefore, superior to selfishness and violence.’” (p. 19). Do you see hope for change in human behavior? What is your suggestion for bettering ourselves? 4. “For near 200,000 years – most of human existence – people survived on cooperative economics and a more classless society, where the life, wealth, and work of the ruler or leader was not significantly different than any other member of the group.” (p.20). “Studies indicate that modern adults are not instinctively selfish—our first impulse is typically to cooperate and care for others.” (p. 21). What happened to us to change and tolerate the divided and oppressive system we have today?  5. “Now that we know society largely determines human nature, rather than

the reverse, there is only one logical question to ask: what kind

of society should we create? (p. 23) What kind of

a society would you like to create? What do you need to move in that

direction?

5. “Now that we know society largely determines human nature, rather than

the reverse, there is only one logical question to ask: what kind

of society should we create? (p. 23) What kind of

a society would you like to create? What do you need to move in that

direction?

6. “Harriet Beecher Stowe, in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, wrote that ‘capitalists’ and slave owners alike were ‘appropriating’ the lower class, ‘body and bone, soul and spirit, to their use and convenience’. The rich man believed ‘there can be no high civilization without enslavement of the masses, either nominal or real.” (p. 30). Do you agree that racism and capitalism work together? Can we eliminate racism without addressing capitalism? 7. “Over ninety percent of our nation’s existence has been marked by war, and surveys indicate people around the world view the United States as the single greatest threat to world peace.” (p. 111). Do you agree? Make that case for or against the US being the greatest threat to world peace. Talk about Vietnam, Mexico, Guatemala, Philippines. (see p. 111) 8. “Socialism also eliminates capitalism from the bottom-up…Under socialism, the exploitation of labor and authoritarian power are consigned to the dustbin of history, replaced by cooperation, equity, and democracy…In the socialist model, work cooperatives are the humane alternative to capitalist businesses. In a cooperative, all workers share equal ownership of the firm. This translates to equality in power and in wealth…Elizabeth Blackwell wrote that Christian socialism would mean labor receiving a fair and increasing share in the profits it helps to create.” (p. 120-122) Can you imagine our country with cooperation, equity, and democracy? How would that be different from the country you experience today? 9. “In truth, the mechanisms and incentives that drive technological, systematic, and other forms of change remain in place in co-ops. Outside inventors can still sell or license their creations to cooperative businesses; start-up founders, while sacrificing total power and wealth hoarding, can still bring their creations to the world, doing what they love and making money off it…Co-ops are also more stable that capitalist firms, even during economic crisis.” (p. 125-126). Have you invested in or participated in a co-op of some form? Describe the experience. What worked for you and what did not work for you? 10. “Imagine living in an America like this…Might we grow, collectively, less greedy and more caring? Less individualistic and more attuned to the needs of all, the common good? (p. 129). When have you experienced life in a less greedy and more caring way? Describe the situation and the benefits of such an arrangement. What can you do to make this happen more often in your life and in your community? Some examples of this are: :: UBI (Universal Basic Income) p. 145f. :: Guaranteed work through public works projects - p. 149f. “Overcoming poverty is not a task of charity, it is an act of justice. Like slavery and apartheid, poverty is not natural. It is man- made and it can be overcome and eradicated by the actions of human beings.” Nelson Mandela said. (p.155) :: Universal Health Care p 156f. “This does not mean the State will own the hospitals and employ the doctors. Instead, the reverse would be true –the doctors, nurses, receptions, and janitors (the workers) would own the clinics and hospitals.” (p. 156) :: Universal Education p. 164f “A socialist society would include free K through 12 education, pre-school and college…democracy would enter education. Teachers, paraprofessionals, librarians, janitors, and other workers would own their schools…Public schools will remain ta- funded and neighborhood-based, following a democratically determined national curriculum.” (p. 164-165)

This book contains

a thorough collection and discussion of the deficiencies of capitalism

and the contrasting advantages of socialism. The book is filled with many

footnoted sources so anyone contemplating writing an essay on this subject

can find numerous information sources within its text.

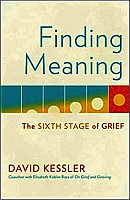

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - June 9 Wednesday 1-2:30pm on Zoom --Notes from last month  Finding

Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief Finding

Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief

David Kessler In 1969, Elisabeth K?bler-Ross first identified the stages of dying in her transformative book On Death and Dying, and decades later, she and David Kessler wrote the classic On Grief and Grieving, introducing the stages of grief. Vern, who leads the discussion in David's absence, studied with Dr Ross at the University of Chicago Hospitals when he was a doctoral student at the time when Life magazine came to the class to see her work with dying patients and her students. We have learned much since then, beyond her "five stages of grief," and the Kessler book promises a useful advancement. Vern tells how he approached a memorial service in May for grieving parents and a brother and an extended family for a baby born in January. Here is what David has prepared to facilitate our discussion: “In 1969, Elizabeth Kubler-Ross identified the five

stages of dying in her groundbreaking book:

“Ultimately, meaning comes through finding a way

to sustain your love for the person after their death while you’re moving

forward with your life.” (p.6-7)

“The need is for someone to be fully present to

the magnitude of their loss without trying to point out the silver lining.”

(p. 29)

“Grief is what’s going on inside of us, while mourning

is what we do on the outside. The internal work of grief is a process,

a journey. It does not have prescribed dimensions and it does not end on

a certain date.” (p.31)

“Pain is inevitable, but suffering is optional.

. . . Pain is the pure emotion we feel when someone we love dies. The pain

is part of the love. Suffering is the noise our mind makes around that

loss, the false stories it tells because it can’t conceive of death as

random.” (p.51)

“The story you tell yourself repeatedly becomes

your meaning. Just as the story I told myself for many years about the

past kept me imprisoned in pain, the story I began to tell myself from

other points of view freed me.” (p. 71)

“I ask them these questions:

How can you honor your loved one? How can you create a different life that

includes them? How can you use your experience to help others? It is in

your control to find meaning every day. You can still love, laugh, grow,

pray, smile, cry, live, give be grateful, be present.” (p. 111)

“The word ‘committed’ is usually

used in the context of crimes. A broken mind is a tragedy, not a crime…He

is Jim who died by suicide.” (p. 116)

“But no matter how deeply

religious or spiritual we are, sometimes we want to be left in the humanness

of our pain. There will be times when a grieving person does not want to

be told that their loved one has gone to a better place or has gotten their

heavenly reward or is with Jesus.” (p. 193). “Not only do we have a need

to feel the pain, we also need to have it witnessed by others, not pushed

away.” (p. 195)

“How do you mend a broken

heart? By connection…human connection can and does actually help with broken

heart syndrome. Perhaps being witnessed helps us physically as well as

emotionally. Our heart longs for connection. Anyone who is going through

deep grief can tell you that grief affects your mind, your heart, and your

body.” (p. 242)

Please

visit Goodreads for the "spoiler."

This book explores

paths toward healing for people overwhelmed by grief. Though the cause

of grief is often death of a loved one, it can also be the result of divorce,

betrayal, or end of a career.

As inplied by this book’s subtitle, the whole world knows about the five stages of grief. (view spoiler) This author has worked together with K?bler Ross since 1969, and in 2004 he coauthored “On Grief and Grieving” with her. If a sixth stage needs to be added, Kessler is in the best position to do so. One of the reasons he was motivated to write this book is the death of his 21-year-old son. In a sense, writing this book is his way of finding meaning in that loss. “Ultimately, meaning comes through finding a way to sustain your love for the person after their death while you’re moving forward with your life. That doesn’t mean you’ll stop missing the one you loved, but it does mean that you will experience a heightened awareness of how precious life is. … In that way we do the best honor to those whose deaths we grieve. … Loss is simply what happens to you in life. Meaning is what you make happen. (p16)”In this book Kessler shares a variety of stories from people he has encountered leading numerous grieving workshops and providing counseling services for private clients dealing with issues related to grief. Many of these stories are emotionally moving about the ways some people have dealt with loss. These stories can perhaps suggest guidance to readers in similar circumstances, but a few of these stories include amazing coincidences of fate resulting from a loss which make for interesting reading but not likely to be applicable in other cases. Kessler adds to these stories by sharing experiences related to the loss of his son. Early in the book, in the Introduction, the author provides the following thoughts that may guide the reader in the understanding of meaning. 1. Meaning is relative and personalEarlier in the book Kessler mentions that the “five stages were never intended to be prescriptive.” This is also true for finding meaning. Some people suffering from grief will not want to think about meaning, and will resent expectations to find it in their grief. Sometimes people say they don’t want to find meaning in their loss. They just want to call a tragedy a tragedy. To find meaning in it would be to sugarcoat it and they don’t want to do that. I think they are afraid that if they let go of the pain, they will lose the connection to their loved one, so I remind them that the pain is theirs and no one can take it away. But if they can find a way to release the pain through meaning, they will still have a deep connection to their child—through love. Just like a broken bone that becomes stronger as it heals, so will their love. (p183)

July 14 Wednesday 1-2:30 p.m. on

new Zoom

-- (Notes from last month)

Waking Up White and Finding Myself

in the Story of Race

This is the book Irving wishes someone had handed her decades ago. By sharing her sometimes cringe-worthy struggle to understand racism and racial tensions, she offers a fresh perspective on bias, stereotypes, manners, and tolerance. 1. “No one

alive today created this mess, but everyone alive today has the power to

work on undoing it. Four hundred years since its inception, American racism

is all twisted up in our cultural fabric. But there’s a loophole; people

are not born racist. Racism is taught, and racism is learned. Understanding

how and why our beliefs developed along racial line holds the promise of

healing, liberation, and the unleashing of America’s vast human potential.”

(xviii). Do you agree? Are you ready to study, ponder,

discuss, and be open to ways of making this a better country?

This book shares

the author's story of living a life of good intentions regarding issues

of racism but admits numerous missteps along the way. She describes it

as "my own two-steps-forward, one-step-back journey away from racial innocence."

The message in this book is from a white author aimed at white readers,

and any resistants from the reader to her message is overcome by a frank

and vulnerable confession of her belated awareness of the realities of

white privilege and systemic racism. The author is suggesting that the

reader may have something to learn from her experiences.

The powerlessness and isolation I felt as a bystander (which I didn’t even realize I was) have been replaced by a sense of empowerment that comes with feeling there’s a critical role for me in dismantling racism. But here’s the catch: it’s trickier than one would think to take on the role of ally and not be, well too white. I should not be in the role to take over, dominate, or be an expert. The role is not for me to swoop in and “fix.” The white ally role is a supporting one, not a leading one. (p.302)One of the things I liked about the book was that it was divided into many short chapters, and at the end of each chapter were questions and suggested exercises. This setup seems to lend itself to encouraging group discussions using the book. The book seemed full of quotable gems, and some that caught my attention are included in this (STOP or continue reading to view spoiler). SPOILER:

#vcAug

What will happen to life when science identifies

the genetic basis of happiness? Who will own the patent? Do we dare

revise our own temperaments? Funny, fast, and magical, Generosity celebrates

both science and the freed imagination. Richard Powers asks us to

consider the big questions facing humankind as we begin to rewrite

our own existence. Generosity tells the story of Thassadit “Thassa”

Amzwer, an Algerian refugee who seemingly has overwhelming happiness

(hyperthymia) written in her genes, and the confounding effects she

has on those around her, both sincere and exploitive. Characters in the

novel include Russell Stone, a minor magazine editor, moonlighting

as a writing instructor, Thomas Kurton, a charismatic entrepreneur

behind Truecyte, a genetics lab, Candace Weld, a school psychologist and

Tonia Schiff, the host of a popular science show called “Over The

Limit”.

1. “I want you to think and feel, not sell. Your writing should be an intimate meal not dinner theater.” (10) Do you write your down your thoughts and feelings? What journal techniques have you discovered to be helpful in your life? I wrote a “Top Ten Reasons I Journal” and it is posted on my blog under “journal resources” in “categories,” if you are interested. 2. “Happiness is probably the most highly heritable component of personality. From 50-80 percent of the variation in people’s average happiness may be accounted for by genes. People display an affective set point in infancy that doesn’t change much over a lifetime. For true contentment, the trick is to choose your parents wisely.” (49). How did you do in the birth lottery? Did you have a happy childhood? 3. “Yet the conflicted book insists on a role for nurture. Joyousness, it says, is like perfect pitch: a little early training in elation can bring out a trait that might otherwise wither.” (49). What is the difference between happiness and joy? Can you share a story of one or the other? 4. “The book says happiness is a moving target, a trick of evolution, a bait and switch to keep us running. The doses must keep increasing, just to break even. True contentment demands that we wean ourselves from all desire. The pursuit of happiness will make us miserable. Our only hope is to break the habit.” (71) Buddhism teaches that the pursuit of happiness adds to our unhappiness. Would you agree? Why was “the pursuit of happiness” included in our nation’s founding documents? 5. “Hyperthymia, a rare condition that programs a person for unusual levels of elation.” (117). Do you anyone who has this condition? What is it like to be around this person? 6. “The novelist’s argument is clear enough: a genetic enhancement represents the end of human nature. Take control of fate, and you destroy everything that joins us to one another and dignifies life.” (149). Do you agree that without an unknown future life would be lessened? Is mystery and the unknown part of what makes human life exciting and an adventure? 7. “The Alzheimer’s gene, that alcoholism gene, the homosexuality gene, the aggressive gene, the novelty gene, the fear gene, the stress gene, the xenophobia gene, the criminal-impulse gene, and the fidelity gene have all come and gone. Bu the time the happiness gene rolls around, even journalists should have long ago learned to hedge their bets. But traits are hard to shake, and writers have been waiting for this particular secret to come to market since Sumer.” (197). Would you be open to the idea of selecting and rejecting certain genes for your offspring? How would you make the choice? 8. “In the last lines of the profile, the scientist says, ‘I don’t believe in God, but I do believe that it’s humanity’s job to bring God about.’” (206) What does that mean to you? 9. “If Jen truly is without sadness, then she’s missing out on something profound, mysterious, and essentially human.” (212) Share your thoughts about sadness as profound, mysterious, and essentially human. Can you share a time of sadness that is important to you? 10. “The day may come when we will choose our children as carefully as we now choose our mates. We may select our natures the way we screen for a career. All the larger, qualifying, problematical follow-up had been clipped away.” (279) We now have lots of dating sites on the web. Can you imagine the day we can pick and choose the traits we want in our children? Create in your imagination the child you would like to parent.