|

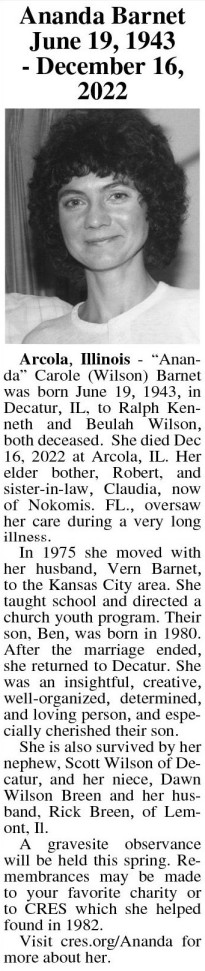

"Ananda" Carole

(Wilson) Barnet

1943-2022

"Ananda" Carole A. (Wilson)

Barnet was born June 19, 1943, in Decatur, IL, to Ralph

Kenneth and

Beulah Wilson, both deceased. She died Dec 16, 2022 at

Arcola, IL. Her elder bother, Robert, and sister-in-law, Claudia, now

of Nokomis. FL., oversaw her care during a very long illness.

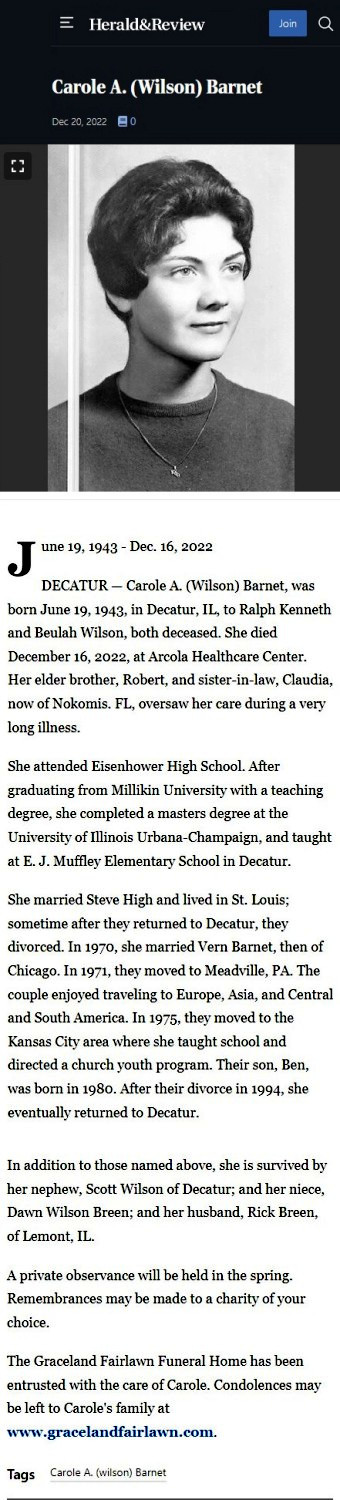

School photo She attended Eisenhower High School. After graduating from Millikin University with a teaching degree, she completed a masters degree at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and taught at E. J. Muffley Elementary School in Decatur. She married Steve High and lived in St. Louis; sometime after they returned to Decatur, they divorced. In 1970, she married the Reverend Vern Barnet, DMn, then of Chicago. In 1971 they moved to Meadville, PA. The couple enjoyed traveling to Europe, Asia, and Central and South America as well as many places in the US. In 1975 they moved to the Kansas City area where she taught school and directed a church youth program, one of which won national denominational recognition.  Many of her friends knew Carole as "Ananda," a name she was given at a yoga retreat which she adopted. She also studied American Indian spirituality and was well-known for her expertise adapting indigenous knowledge and rituals for the wider community. She was certified in Senoi dreamwork and trained professionally in Transactional Analysis and Gestalt awareness techniques, and stayed current with research as she assisted others with personal and spiritual growth. She was a remarkable teacher who could convey both the substance and the feeling of whatever subject she addressed and was a frequent guest on local radio. She helped found CRES in 1982 and was its first program director. In 1984, she said this: The purpose of CRES is not to glamorize or romanticize peoples of exotic religions. CRES does not set these religions above our and imply that people who practice them are perfect. They are human just as we are, and are subject to cultural stresses and personal foibles as we all are. To put people of another religion or culture on a pedestal is to stereotype and therefore dehumanize them, just as much as if we were to generalize about them in an insulting, uninformed way. We believe that we all have something to contribute to human consciousness. While we do not need to give up our own path, we can find it enriched and broadened by opening ourselves to the experience of others who may have perceptions of the world different from our own. We want to make understanding of the world's religions accessible to many people, not only in our "heads" but in our 'hearts" -- to move from mere tolerance to appreciation; and in so doing, enrich our lives and contribute to world peace.  Among her many talents was the light touch she could give even a profound topic, as in this essay about an encounter in Tokyo at a Japanese Tea House. With endless curiosity and prodigious energy and abilities, for a time she managed an art gallery specializing in Southwest art, and was featured in The Kansas City Times (later merged with The Star) for her oriental cooking. Their son, Ben, was born in 1980. After the marriage ended in 1994, she eventually returned to Decatur. She was an insightful, creative, well-organized, determined, and loving person, and especially cherished their son. In addition to those named above, she is survived by her nephew, Scott Wilson of Decatur, and her niece, Dawn Wilson Breen and her husband, Rick Breen, of Lemont, Il. A gravesite observance will be held in the spring. Remembrances may be made to a charity of your choice, to Psychiatry/KU Endowment–Medical Center or to CRES which she helped to create. CRES Box 45414 Kansas City, MO 64171 email address vern@cres.org This runs through Ben's thoughts -- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YBcdt6DsLQA In My Life -- the Beatles Arrangements by GracelandFairlawn in Decatur, IL., (217) 615-0724 -- gracelandfairlawn.com. Obitury at the GracelandFairlawn website. Obituary at the Decatur Herald&Review Mirror Herald&Review Obituary in The Kansas City Star Dec 25, 2022. #AnandaTea This article was featured in the first issue of 1984, the second year of The Release, the publication of CRES, which became Many Paths when the Interfaith Council was formed in 1989. You can download a four-page PDF here. MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING or ZEN AND TEAISM Ananda Barnet with thanks to the Rev Yoshikazu Matsuda and Keiko Matsuda the Rev Yoshiyuki Hasegawa and family Hisashi Yamada I, a confirmed and incorrigible coffee drinker, had long secretly suspected that tea was nobler than coffee, although I had no proof of it. In the small Midwest town where I grew up, just the opposite supposition was held to be true; tea and tea drinkers were suspected of the worst sin, being unpatriotic, for wasn’t it tea that had been thrown into Boston Harbor? And to drink tea, if one were a man, surely meant one did so with a kinked pinky, putting on airs of sophistication not appreciated by common folk. But the bottom line was that tea made one’s manhood suspect. I didn’t have to worry about my manhood, so this powerful symbolism passed me by. But as I walked along the bustling streets of Tokyo, headed for a teahouse with my husband and a Konko-kyo minister with whom we were staying, I wondered “What the folks back in my home town” would think of my excursion. Enough, they would say, that I had bought a Toyota. It was inevitable that I would to this, so their theory goes. Fondly, I chided them in my mental chatter, I sniffed, “You all too much tea in you.” By this I understood the Japanese to mean that they were too caught up in the dramas of life. The opposite of this was someone with too little tea who is cold and insensitive and lacking compassion. I wondered if finding balance and harmony was the essence of the tea ceremony, not too much, not too little. I could always use a little balance and harmony, myself. As I carried on my internal dialog, lost in thought, the streets around me were alive with a cacophony of sounds and sights and smells that played on my chattering nerves that had already been hard pressed with a sensory overload. We spoke no Japanese, and our host, who could speak no English, walked silently, looking neither left nor right. It was he who had arranged this session with a tea master who was a member of his congregation. We had been told by mutual Japanese friends, who did speak English and served as our interpreters, that it was a rare opportunity to be invited to participate in this ceremony, not open to tourists. Our Japanese friends had themselves never attended a session and envied us this opportunity. We felt honored, but a little intimidated, having been only briefly versed in tea ceremony protocol. Suddenly our host paused in his tracks and motioned us to follow him. Stepping off the city sidewalk, we turned onto a path of irregular stones. Moss covered granite lanterns appeared like apparitions out of nowhere. Evergreens and ferns encompassed us as much as if we had entered a deep forest. Sounds of the city melted away. My mental noise halted as if shocked out of my head and I felt a wave of calm envelop me as my mind focused with intrigue on my bucolic surroundings. Just as suddenly as the street had disappeared, turning a bend in the path brought forth, some yards ahead of me in a clearing, what looked to be a rustic thatched peasant hut. At first glance I was reminded of the fairy tale straw house of one of the three little pigs. As a child I had been taught by this tale that no matter how charming, it was folly to construct a house that might be so impermanent as that made of straw. One must build a big strong house of brick like the wise little pig who kept the wolf from his door. In doing so one would not feel so little, scared and defenseless against the big bad wolves of the world. I was learning to read this story just about the time that the first nuclear bombs went off. As we drew closer, what had seemed at first glance like an unpretentious cottage held an aura that was the result of profound artistic forethought, each aspect designed with care to detail and interrelationships. It was exquisite, even to someone who was not a connoisseur. I was not surprised when I later learned that the hut was built by master craftsmen who searched far and wide for the finest materials and then put these together, polishing each beam and board as a form of meditation. As a result, this simple structure, which at first glance seemed to be one of genteel poverty, was supremely sturdy and cost more to build in time and money than the mansion of a wealthy person. Standing on the polished cedar steps was a man dressed in a cotton kimono waiting to greet us. He had a radiance that might well glow in the dark. As we approached he made a low meditative bow and slowly pressed his hands together as if in prayer, greeting us in Japanese, “Ohayo.” “Good morning,” we returned the greeting, for it was morning and the sun was barely up and the dew had not yet left the ground. Awkwardly we bowed and, sitting on a bench, took off our shoes, putting on the slippers he gave us. Humbly and carefully he placed our shoes in a neat row on the porch. We then followed him into the hikae noma, the room where guests wait until they receive the summons to visit the tea room. When we entered we were directed by a gentle man in Western garb who was to be our interpreter. Although he was the tea master, a student would present the ceremony and it would be his role to guide us through. We would not have the services of the grand master, not only because he did not speak English, but because he only did the ceremony for famous actors and other public figures. However, we were fortunate in that this tea master, who was to initiate us in the way of tea, had traveled extensively in the United States and was used to the clumsy ways of foreigners. He was here for only a brief time. He spoke impeccable English and we were delighted with his meticulous patience. As we were directed to the low wooden platform recessed into the wall called a tokonoma, we, one by one, gave attention to a scroll and flower arrangement specifically designed for this time and space and put in this place of honor. It was the custom of the tea house to spend time admiring these objects — how they were formed, their shapes, their beauty, the skills of the person who made them — and to contemplate the meaning of the calligraphy on the scroll. I knelt and looked, feeling a little foolish with false veneration, like a 12-year old telling her teacher she liked Shakespeare. I knew it was lovely, but I also knew there were depths which my inexperienced eye would not be able to plumb. When we took our seats on simple benches, the host, who would take us through the ceremony, pointed out that the two Chinese characters on the scroll meant “dew” in one sense, and in another, Zen, sense, “appreciating the moment.” He went on to explain that appreciating the moment was what it meant to be in a tea house. There is nothing else. There is only now. Everything we need for fulfillment is right here because it is inside of us. Going into a tea house is going inside of ourselves. Everything that is in the universe is within us, and we need go no further to find contentment and wholeness. We need not go anywhere or do anything. All conversation and thoughts in the tea house focus on what is going on right now. To the side of the room I noticed that there was an open wall with the bamboo shades rolled up. Outside this window, framed by polished cypress beams, was a most peaceful moss and fern and evergreen garden. Ever observant, the tea master noticed my eyes rest on this view and he noted that usually the shades were rolled down because the outside world is to be entirely shut out as we go into ourselves. I returned my gaze to a room devoid of ornamentation, a decompression chamber to prepare us for going into the tea room. Nothing was here except what was needed to satisfy the needs of the moment — an effort to create in ourselves a vacuum so that words will not get in the way of experience. It was a simple room, but designed with a sense of harmony. It was satisfying. I wanted to wash my mind free of words and open myself to pure awareness which I knew could be done in rare moments. Although this direct experience was what I wanted to happen, instead my “monkey mind” conjured up words about Zen and the tea ceremony. The essence of the tea ceremony is Zen. To talk about tea is to talk about Zen which can’t be talked about any more than my words can give the reader the experience of sitting in the tea house. The tea ceremony was developed as a Zen ritual instituted by monks who successively drank out of a bowl before the image of Bodhidharma. All great tea masters are students of Zen and the spirit of Zen is introduced into the actualities of life. Zen accepts and celebrates the mundane, and is the art of being in the world as it is. “The organization of the Zen monastery is very significant of this point of view. To every member, except the abbot, was assigned some special work in the care-taking of the monastery; and curiously enough, to the novices were committed the lighter duties, while to the most respected and advanced monks were given the more irksome and menial tasks. Such services formed part of the Zen discipline and every least action had to be done absolutely perfectly. But paradoxically, Zen masters knew that there was no such thing as perfection. It was the process of striving for it that was important. The whole ideal of Teaism is a result of this Zen conception of greatness in the smallest incidents of life [Okakura, page 28].” To do what needed to be done and do it well. When a Zen master was asked by a disciple to explain to him the essence of Zen, the master responded, “Are you done eating?” “Yes,” replied the puzzled disciple. “Then wash your bowl.” And that summed up Zen. We stood at the open door of the hikae noma facing the path of stepping stones thru the lovely garden I had seen through the window. These stones would lead us to the tea room. The man who had first greeted us noiselessly appeared with straw sandals which we exchanged for the slippers we were wearing for our walk through the garden. As we stepped onto the first few stones we noticed that the path forked, and one path led to the tea house and the other path led into the evergreens to we knew not where. The tea master explained that if we saw a small rock with a string around it on the path to the tea house that meant the tea house was closed to us and we must take the other path which led back into the street. A moment of fear crossed my mind as I was now thoroughly intrigued with the possibility of participating in the tea ceremony but feared it would be closed to us by some quirk of fate. We saw the rock with the string on it, but it was placed on the stones of the path that led to the street. We could proceed to the tea house. First we needed to stop at the fork in the path where there was a stone fountain across which was placed a bamboo dipper. We were told the water was the purest. We were instructed by the tea master on the correct way to purify ourselves with the dipper of water. He scooped water into the bamboo cup, holding it first with his right hand and pouring half of it over his left. Then he reversed the procedure, cleansing his right hand. Taking another scoop, he took a drink to cleanse his mouth. Yet a third scoopful he tilted back to let the water run down the handle which purified the dipper, too. We three purified ourselves and the dipper each in turn. As we reached the door to the tea room we were once again offered slippers in exchange for our straw sandals. One by one we noiselessly entered the door, stooping over as it was only three feet high. In our stooping we were to leave false pride, pretensions, haughtiness and vanity behind — in other words, our ego which separates us one from the other. We were to leave aside expectations that make all experience monotonously the same. When we superimpose from the past our precepts, conventions, traditions, and limitations, we taint our experience. If I had been a samurai I would have left my sword at the door; but, having no sword to leave, I left all thoughts of aggression. As I entered I became no better or worse than the lowliest peasant or the greatest daimyo. (A contradiction I find puzzling, however: if this be the theory, then why does a leading tea master save himself for only the famous? What difference does it make? But I did not think about this question until later. And I found no answer.) My attention was once again riveted on a tokonoma with a vase of flowers and some calligraphy done in supreme beauty and simplicity as a meditation. We were directed to it to salute it in the place of honor and then to a neat row of three soft pillows so that we guests sat side by side with our host sitting to one side partially facing us. He told us to be sure to find a comfortable position so that we could sit quietly for a long period of time. Quiet reigned except for the soft sound of boiling water in an iron kettle off in the anteroom. Later I learned pieces of iron had been arranged in the bottom of the kettle so it would sing to us of murmuring wind through the pines or perhaps a bubbling brook. I thought of the soft sighs of my basset hound breathing on the other side of the world, and other gentle associations the tea kettle raised within me. The host said that all our thoughts should be on the tea ceremony about to be experienced. No thoughts of the world or anything that is not happening now. My mind returned to the room which was calm in tone as were the clothes we had chosen to wear for the occasion -- all unobtrusive. There was a sense of all having mellowed with age yet immaculately clean. There was not a particle of dust to be found. A particle of dust meant our host was not a tea master. In this connection there is a story of Rikyu which well illustrates the ideas of cleanliness entertained by the tea-masters. “Rikyu was watching his son Sho-an as he swept and watered the garden path. ‘Not clean enough,’ said Rikyu, when Sho-an had finished his task, and bade him try again. After a weary hour the son turned to Rikyu, ‘Father, there is nothing more to be done. The steps have been washed for the third time, the stone lanterns and the trees are well sprinkled with water, moss and lichens are shining with a fresh verdure; not a twig, not a leaf have I left on the ground.’ ‘Young fool,’ chided the tea-master, ‘that is not the way a garden path should be swept.’ Saying this, Rikyu stepped into the garden, shook a tree and scattered over the garden gold and crimson leaves, scraps of the brocade of autumn! What Rikyu demanded was not cleanliness alone, but the beautiful and the natural also [Okakura, page 36].” A door opened to the left and a lovely young woman dressed in a quiet kimono entered silently with slow graceful steps. She stood before us holding a tray of three bowls. She bowed low. We returned the bow. She presented a bowl to me. I bowed from the waist as I had been instructed earlier, accepted it and set it to my left. Bowing to the person to my left I said, “Excuse me for going before you.” Picking up the bowl I admired it as a work of art should be admired. It had a solid feel in my hand and was ever so slightly lopsided. The colorations were earth tones of browns and grays with a semi-luster. It was as unpretentiously lovely as a freshly plowed field. Only after I had eaten my sweet was my husband served, and then in turn when he was done our friend was served and both responded just as I had. The sweet was cool and refreshing for it was summertime. (The nature of the sweet changes with the season, the lightest, coolest sweets being served in the summertime.) With more bowing, the bowls were graciously removed and the student who was serving us now entered with a tray of bowls and a tea pot. Her movements were as disciplined as the finest ballet dancer, performed simply and naturally. There were no superfluous movements, no energy wasted. Later I found out how difficult this was when I tried to imitate her presentation to some friends at home and realized what economy of moves she had. She had been choreographed. I didn’t know the dance. I felt like a novice out of the audience who had gotten onto the stage saying pretentiously, I’ll show you how Margot Fontaine does it. Later I learned that different schools followed different routines and there were variations on the same theme. But all of them took years of discipline to make it look so simple. Serenity of mind must be maintained. As a Noh actor, a tea master or mistress must live his or her art, must be living art, for everything done is an expression of self. Along with her tea caddie and bowls she had on her tray a water jar, tea spoon and ladle and tea whisk of bamboo, a water jar, washing bowl, tea bowls, tea and a fukusa (a red silk napkin). Although the objects in the tea ceremony had been meticulously cleaned before the ceremony, she, kneeling beside the tray, wound the fukusa around her fingers and ritually cleaned all utensils, demonstrating concern for the guests, respect for the utensils and the host’s willingness to serve. After the cleaning of the serving items she ceremoniously cleaned her hands and mouth and the ladle as we had done at the fountain before entering the tea house. She ladled hot water into the tea bowl, placed the whisk in the hot water and then examined the whisk to be sure each tine was unbroken and properly distanced one from the other. Just as the sweet was served to the guests one at a time, so was the bowl of tea which she whisked first into a green froth. After excusing myself and turning the bowl, I drank the bitter brew in a few swallows. I was told later that unlike caffeinated teas, this one had a mellowing effect. The tea bowl was removed, washed and the same bowl was reused by the other two guests. When all had completed the drinking of the tea, the bowl was passed around for admiration. Discussion focused on the utensils and questions asked of the host (prompted by the host) such as, “How old are they? Where did they come from?” After the utensils were discussed, we were told that it was appropriate to discuss the experience. I felt some urgency to say something profound, but realized with humility I had nothing profound to say except to share my experience. What I clumsily expressed was that to me the experience was as if I had been inside a work of art, not observing, but actually being a part of that work of art — and it was not either a visual or an auditory experience, but had both of those elements plus kinesthetic, olfactory and taste so that all the senses were involved and came alive. The tea master smiled as enigmatically as the Mona Lisa. The tea ceremony is always successful for there is no other way but “the Way.” It did not matter what we “got out of it.” What we “got” or “didn’t get” was fine. The utensils were removed to the preparation room. The host bowed to us. We bowed to him and to each other and stepped one at a time to the tokonoma, commenting upon its beauty. I tried to remember what the tea master had said was meant by this bit of calligraphy. He told me once again, but I cannot now remember. Years later I occasionally wonder what it said. It seemed wonderful at the time. Stooping low I went back through the doorway wondering if my ego was going to find me again. It did — but sometimes I remember what it was like for those few minutes without it. I put on the straw sandals for the brief stroll back through the garden, and then changed once again into slippers and returned to the waiting room. The room seemed strangely transformed and yet familiar as if I had spent a lot of time there when actually the whole experience had not been much more than an hour. We took our seats on the benches and spent a few more moments discussing our experience with the master. He returned us to the porch where our shoes were presented to us by the man who had originally taken them from us. We bowed deeply and said softly, “Ohayo.” We came full circle and returned to the world, down the moss lined path into the jangling city streets. My thoughts came slowly, evenly now, not tumbling on top of each other, not crowding in upon me. The precision of the ceremony left me feeling very sane. In a seemingly chaotic world we had touched some harmony and order which reigned through all things. I thought of William Blake’s quatrain, “To see the world in a grain of sand and a heaven in a wild flower, hold infinity in the palm of your hand and eternity in an hour.” “To see a heaven in a wild flower” — As I was walking the city streets, I remembered The Book of Tea by Kakuzo Okakura. I was struck by the story he told about a tea master who was famous for his morning glories. As I thought of it, the story seemed to get to the essence of the ceremony itself. The tea ceremony spawned the art of flower arranging. The Buddhist monks gathered flowers after a storm and in their compassion for living things, placed them in vases of water so that they might live on. Later tea masters carefully selected a branch or spray which they culled with an eye for artistic composition. They were ashamed if they cut more than necessary. They arranged them reverently and placed them on the tokonoma, the place of honor. In

the sixteenth century the morning-glory was as yet a rare plant with

us. Rikyu had an entire garden planted with it, which he cultivated

with assiduous care. The fame of his convolvuli reached the ear of the

Taiko, and he expressed a desire to see them, in consequence of which

Rikyu invited him to a morning tea at his house. On the appointed day

the Taiko walked through the garden, but nowhere could he see any

vestige of the convolvulus. The ground had been leveled and strewn with

fine pebbles and sand. With sullen anger the despot entered the

tea-room, but a sight awaited him there which completely restored his

humor. On the tokonoma, in a rare bronze of Sung workmanship, lay a

single morning-glory — the queen of the whole garden! [Okakura, page

60]. When I first read this story, I was shocked and outraged — appalled at this wanton waste, this massacre. Yet I was fascinated as by a mass murder. What kind of mind would do such a thing especially in the context of Buddhist reverence for life? It was one of those paradoxes that left me bewildered. Upon reflection some questions arose in my mind. How often do we level beauty by our lack of awareness? And how often do we ruthlessly take great gobs of flowers, stick them in bouquets and barely look at them? How often do we look at beauty and not really see it? This is wanton waste. But what the tea master did was of a different order. He was a master of seeing. I cannot ever look at the morning glories cascading over my fence every summer without thinking of the story of the devastation and all but that one true morning glory. The tea master helped me see them better. The tea ceremony has that power to focus us for that one brief moment and make the senses come alive. And just as the briefness of the tea ceremony reminds us of our own brief span on the earth, so the tea hut, like the body, is only a temporary refuge. There is no place to hide from life. And no place to hide from death. The sacrifice of the flowers is to acknowledge our own impermanence. No, tea was not nobler than coffee. That was nonsense. I had merely drunk so much coffee I had forgotten how to taste it. Perhaps it was time I savored a cup without the distractions of reading or conversation. Perhaps this was true of other things as well. Perhaps all life was art, if we only opened ourselves to experience it more fully. The expanded moment where we transcend the self could be more than a vague memory. As I walked down the city streets I looked around me, my senses opened to all that was around me, flowing through me like tea. Bibliography Kapleau, Philip. The Three Pillars of Zen. Beacon Press, 1965. Okakura, Kakuzo. The Book of Tea. Dover Publications, Inc., 1964. Suzuki, D. T. Manual of Zen Buddhism. Grove Press, Inc., 1960. Urasenke School of Tea Cha-no-yu. No publisher indicated or date. © 1984 CRES Box 45414, Kansas City, MO 64171 #StarObit Kansas City Star, Dec 25, 2022, page 26  Decatur Herald&Review  OnLine version at the Kansas City Star: https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/kansascity/name/ananda-barnet-obituary?id=38452891 |